The Asia Network to End FGM/C is proud to share the launch of three newly published study reports, supported by the South and Southeast Asia Research Innovation Hub (SSEARIH), the Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO), and the UK Government.

These reports are part of a broader Southeast Asia–wide research series that examines Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting (FGM/C) practices across the region, with in-depth focus on Indonesia and Malaysia.

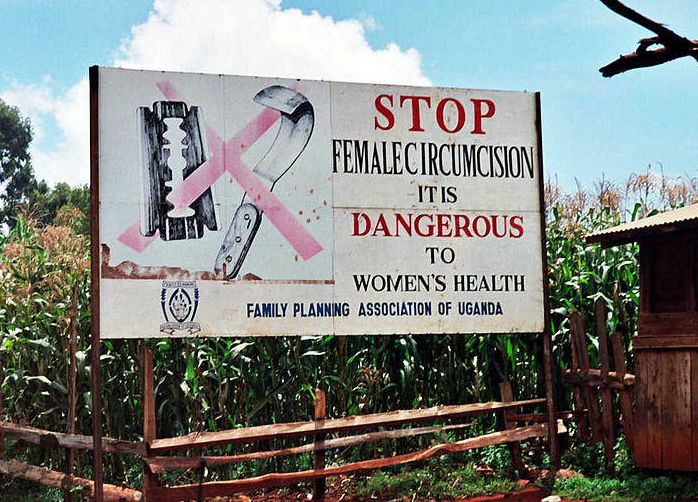

Female Genital Cutting (FGC) is internationally recognised as a grave violation of human rights, impacting the sexual and reproductive health and rights of women and girls. Globally, 230 million women and girls across 90 countries have been subjected to FGC, with Asia accounting for an estimated 35% of this burden, or about 80 million cases. Indonesia and Malaysia together account for more than one-third of Asia’s total, with approximately 70 million affected in Indonesia and 7.5 million in Malaysia. Despite the scale, FGM/C remains under-researched, under-addressed in national policies, and often normalised through cultural traditions, religion, and healthcare practices.

These reports examine the practice of Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting (FGM/C) in Indonesia and Malasia as part of a wider study across Southeast Asia. It explores the prevalence, trends, drivers, norms, and barriers to change associated with FGM/C. The research includes detailed case studies conducted within selected communities to provide localised insights and contextual understanding.

Download the reports here

Download the Policy Brief here.

Download the Malaysia Country Profile here.

Download the Indonesia Country Profile here.

About ARROW

ARROW is a regional non-profit women and young people’s organization based in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. It was established in 1993 upon a needs assessment arising out of a regional women’s health project, where the originating vision was to create a resource center that would ‘enable women to better define and control their lives.

About Orchid Project

Orchid Project is an international NGO, with offices in Nairobi and London, working at the forefront of the global movement to create a world free from FGM/C. At the heart of our mission are grassroots organisations that are pioneering change, and by working together, one step at a time, we believe we can help to end FGM/C globally.

About the Asia Network to End FGM/C

The Asia Network to End Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting (FGM/C) is a group of civil-society actors, led by ARROW and Orchid Project, working across Asia to end all forms of FGM/C. It does this by connecting, collaborating and supporting Asian actors and survivors to advocate for an end to this harmful practice. The Network comprises almost 100 members across 12 countries in the Asia region. Members are activists, civil society organisations, survivors, researchers, medical professionals, journalists and religious leaders, who are committed to working collaboratively together to promote the abandonment of all forms of FGM/C across the Asia region.